Least absolute deviations(L1) and Least square errors(L2) are the two standard loss functions, that decides what function should be minimized while learning from a dataset.

L1 Loss function minimizes the absolute differences between the estimated values and the existing target values. So, summing up each target </span> value \( y_i \) and corresponding estimated value \( h(x_i) \), where \( x_i \) denotes the feature set of a single sample, Sum of absolute differences for ‘n’ samples can be calculated as,

On the other hand, L2 loss function minimizes the squared differences between the estimated and existing target values.

As apparent from above formulae that L2 error will be much larger in the case of outliers compared to L1. Since, the difference between an incorrectly predicted target value and original target value will be quite large and squaring it will make it even larger.

As a result, L1 loss function is more robust and is generally not affected by outliers. On the contrary L2 loss function will try to adjust the model according to these outlier values, even on the expense of other samples. Hence, L2 loss function is highly sensitive to outliers in the dataset.

We’ll see how outliers can affect the performance of a regression model. We are going to use pandas, scikit-learn and numpy to work through this. I’d highly recommend to have a look at the ipython notebook containing the code on this post.

We’ll be using Boston Housing Prices dataset and will to try to predict the prices using Gradient Boosting Regressor from scikit-learn. You can downloaded the dataset directly from UCI Datasets or from this csv.

We are goint to start with reading the data from the csv file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from sklearn.cross_validation import train_test_split

from sklearn.ensemble import GradientBoostingRegressor

from statsmodels.tools.eval_measures import rmse

import matplotlib.pylab as plt

# Make pylab inline and set the theme to 'ggplot'

plt.style.use('ggplot')

%pylab inline

# Read Boston Housing Data

data = pd.read_csv('Datasets/Housing.csv')

# Create a data frame with all the independent features

data_indep = data.drop('medv', axis = 1)

# Create a target vector(vector of dependent variable, i.e. 'medv')

data_dep = data['medv']

# Split data into training and test sets

train_X, test_X, train_y, test_y = train_test_split(

data_indep, data_dep,

test_size = 0.20,

random_state = 42)

Regression without any Outliers:

At this moment, our housing dataset is pretty much clean and doesn’t contain any outliers as such. So let’s fit a GB regressor with L1 and L2 loss functions.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

# GradientBoostingRegressor with a L1(Least Absolute Deviations) loss function

# Set a random seed so that we can reproduce the results

np.random.seed(32767)

mod = GradientBoostingRegressor(loss='lad')

fit = mod.fit(train_X, train_y)

predict = fit.predict(test_X)

# Root Mean Squared Error

print "RMSE -> %f" % rmse(predict, test_y)

With a L1 loss function and no outlier we get a value of RMSE: 3.440147. Let’s see what results we get with L2 loss function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# GradientBoostingRegressor with L2(Least Square errors) loss function

mod = GradientBoostingRegressor(loss='ls')

fit = mod.fit(train_X, train_y)

predict = fit.predict(test_X)

# Root Mean Squared Error

print "RMSE -> %f" % rmse(predict, test_y)

This prints out a mean squared value of RMSE -> 2.542019.

As apparent from RMSE errors of L1 and L2 loss functions, Least Squares(L2) outperform L1, when there are no outliers in the data.

Regression with Outliers:

After looking at the minimum and maximum values of ‘medv’ column, we can see

that the range of values in ‘medv’ is [5, 50].

Let’s add a few Outliers in this Dataset, so that we can see some significant

differences with L1 and L2 loss functions.

1

2

3

4

# Get upper and lower bounds[min, max] of all the features

stats = data.describe()

extremes = stats.loc[['min', 'max'],:].drop('medv', axis = 1)

extremes

Now, we are going to generate 5 random samples, such that their values lies in the [min, max] range of respective features.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

# Set a random seed

np.random.seed(1234)

# Create 5 random values

rands = np.random.rand(5, 1)

rands

# Get the 'min' and 'max' rows as numpy array

min_array = np.array(extremes.loc[['min'], :])

max_array = np.array(extremes.loc[['max'], :])

# Find the difference(range) of 'max' and 'min'

range = max_array - min_array

# Generate 5 samples with 'rands' value

outliers_X = (rands * range) + min_array

outliers_X

array([[ 17.04578252, 19.15194504, 5.68465061, 0.19151945, 0.47807845, 4.56054001, 21.49653863, 3.23572024, 5.40494736, 287.356192 , 14.40028283, 76.27278363, 8.67066488],…, [ 69.40067405, 77.99758081, 21.73774005, 0.77997581, 0.76406824, 7.63169374, 78.63565097, 9.70691596, 18.93944359, 595.70732345, 19.9317726 , 309.64280598, 29.99632329]])

1

2

3

# We will also create some hard coded outliers

# for 'medv', i.e. our target

medv_outliers = np.array([0, 0, 600, 700, 600])

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

# Change the type of 'chas', 'rad' and 'tax' to rounded of Integers

outliers_X[:, [3, 8, 9]] = np.int64(np.round(outliers_X[:, [3, 8, 9]]))

# Finally concatenate our existing 'train_X' and

# 'train_y' with these outliers

train_X = np.append(train_X, outliers_X, axis = 0)

train_y = np.append(train_y, medv_outliers, axis = 0)

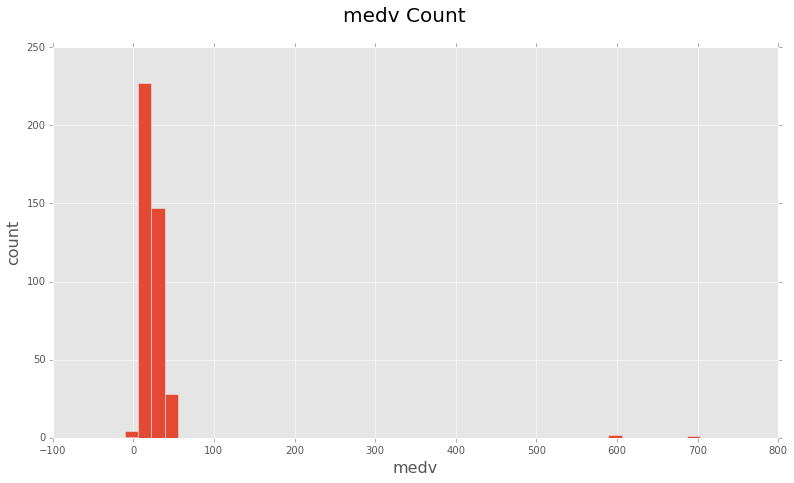

# Plot a histogram of 'medv' in train_y

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(13,7))

plt.hist(train_y, bins=50, range = (-10, 800))

fig.suptitle('medv Count', fontsize = 20)

plt.xlabel('medv', fontsize = 16)

plt.ylabel('count', fontsize = 16)

You can see there are some clear outliers at 600, 700 and even one or two ‘medv’

values are 0.

Since, our outliers are in place now, we will once again fit the

GradientBoostingRegressor with L1 and L2 Loss functions to see the contrast in

their performances with outliers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

# GradientBoostingRegressor with L1 loss function

np.random.seed(9876)

mod = GradientBoostingRegressor(loss='lad')

fit = mod.fit(train_X, train_y)

predict = fit.predict(test_X)

# Root Mean Squared Error

print "RMSE -> %f" % rmse(predict, test_y)

We get a RMSE value of 7.055568, with L1 loss function and existing outliers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# GradientBoostingRegressor with L2 loss function

mod = GradientBoostingRegressor(loss='ls')

fit = mod.fit(train_X, train_y)

predict = fit.predict(test_X)

# Root Mean Squared Error

print "RMSE -> %f" % rmse(predict, test_y)

On the other hand, we get a RMSE value of 9.806251, with L2 loss function and existing outliers.

With outliers in the dataset, a L2(Loss function) tries to adjust the

model according to these outliers on the expense of other

good-samples, since the squared-error is going to be huge for these outliers(for

error > 1). On the other hand L1(Least absolute deviation) is quite resistant to

outliers.

As a result, L2 loss function may result in huge deviations in some of the

samples which results in reduced accuracy.

So, if you can ignore the ouliers in your dataset or you need them to be there, then you should be using a L1 loss function, on the other hand if you don’t want undesired outliers in the dataset and would like to use a stable solution then first of all you should try to remove the outliers and then use a L2 loss function. Or performance of a model with a L2 loss function may deteriorate badly due to the presence of outliers in the dataset.

Whenever in doubt, prefer L2 loss function, it works pretty well in most of the situations.